A Group of Civil War Infantry Soldiers with Rifles, Muskets and Artillery.

Photo: Mathew Brady Collection.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Still Picture Branch; College Park, Maryland.

There were several notable advances in ordnance during the Civil War period. For one thing, this was the first war where widespread use of rifles by infantrymen occurred. Rifled muzzle-loading muskets gradually replaced the smooth bore muzzle-loading muskets that were issued at the beginning of the war. Finally, near the end of the war, breech-loading rifles became available. Before this, rifles had been in limited use and were not generally available for use by infantrymen. Improved manufacturing methods made rifling the bore easier and rifles replaced muskets by the end of the war. Rifling increased the range and accuracy of firearms substantially and may have had a significant effect on the high number of fatalities in the war. Later in the conflict, repeating rifles became common.

At the beginning of the war, most infantrymen were equipped with muskets that had to be muzzle-loaded. It was expected that with good training most infantrymen could load, aim and fire their weapons three times in one minute. Musket ammunition consisted of paper cartridges that contained a pre-measured amount of powder and the projectile. The infantrymen would bite the end off the cartridge, pour the powder in and stuff in the paper as wadding. Then they put the shot in and tamped it down. After the revolutionary metal cartridge and new rifle designs became available, infantrymen could fire as many as nine times more shots in one minute.

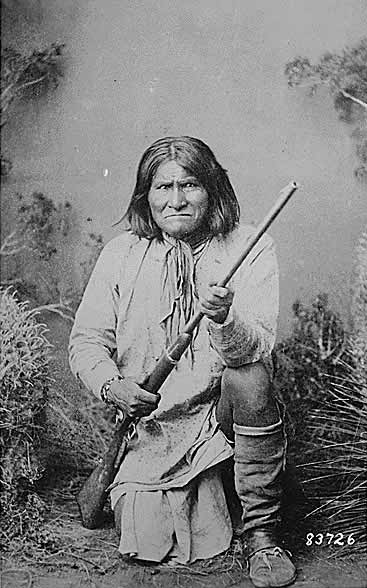

Geronimo (Goyathlay), a Chiricahua Apache Kneeling with Rifle, 1887.

Photo: Ben Wittick - War Department.

US Army Signal Corps, Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

National Archives and Records Administration.

Still Picture Branch; College Park, Maryland.

B. Tyler Henry was granted a patent for a lever-action-repeating rifle on 16 October, 1860. The design was an improvement on the earlier volcanic rifle. It used newfangled mass-produced metallic rim-fire cartridges for ammunition. The Henry rifle held twelve shots in its magazine and another round could be loaded into the chamber. The Henry rifle was the first magazine equipped weapon ever used by the army and it could fire twenty-five shots per minute. The Henry rifle was the direct ancestor of the Winchester rifles that would be widely used after the Civil War, particularly in the wars against native Americans.

Christopher Spencer patented another improved rifle design that came along during the same year. He obtained a patent on 06 March, 1860. The Spencer rifle was accepted more readily by the US Army and came into wider use during the Civil War although some firearms aficionados feel that the Henry was actually a better weapon.

Spencer and Henry rifles revolutionized firearms design by using manufactured metal cartridges for ammunition. Both the Spencer and the Henry could be loaded in a fraction of the time required to load a musket. However, the Henry rifle took a little longer to load than the Spencer rifle, but it had a twelve-shot magazine. The Henry rifle used more powerful ammunition than the Spencer rifle did.

Tyler Henry never really profited much from his invention and the enterprise was taken over by his employer, Oliver Winchester, a Connecticut shirt-maker. Winchester, however, profited greatly from Henry's invention and became very rich operating the Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

After the Civil War, the Spencer rifle lost out to the advantages of the Henry and the Spencer Company went bankrupt in 1869. The New Haven Arms Company of New Haven, Connecticut manufactured the Henry rifle. The New Haven Arms company dissolved in 1866 and was reformed into the Winchester Repeating Arms Company that same year. A few Henry .44 caliber rifles, Model 1860, were made during the Civil War. The Henry Model 1860 was later improved and became the Winchester Model 1866, a widespread consumer product in the American frontier after the war.